Physical death is only one form of dying.

There are other forms of dying:

We die whenever fear governs our choices.

We die when we sacrifice growth for security.

We die whenever we choose a convenient certainty over an inconvenient mystery.

James Hollis, A Life of Meaning

I know you miss the world, the one you knew

The one where everything made sense

Because you didn’t know the truth,

That’s how it works

’Til the bottom drops out and we learn

We’re all just hunters seeking solid ground…

Sara Bareilles, Orpheus

For my whole life, I have tried to be good, to be a good student and a good sister and a good daughter, and to protect my mother and never make her upset or angry…. Now I have added a new tragedy to her life, to our family’s life, and there’s nothing I can do to stop it.

Tatiana Schlossberg (1990 – 2025)

I was deeply saddened to read about the untimely death last week of Tatiana Schlossberg who died at the age of 35 on December 30, 2025, after fighting leukaemia.

She was an environmental journalist for the New York Times and other publications, and she captured hearts just last month with an essay in The New Yorker that detailed her experience with cancer.

Schlossberg is also being remembered as the daughter of Caroline Kennedy and the granddaughter of President John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

Immediately after receiving her diagnosis of acute myeloid leukaemia, she wrote in an essay published in The New Yorker: “I did not — could not — believe that they were talking about me. I had swum a mile in the pool the day before, nine months pregnant. I wasn’t sick. I didn’t feel sick. I was actually one of the healthiest people I knew. I regularly ran five to ten miles in Central Park. I once swam three miles across the Hudson River — eerily, to raise money for the Leukaemia and Lymphoma Society…”

“I work as an environmental journalist, and for one article I skied the Birkebeiner, a fifty-kilometre cross-country race in Wisconsin, which took me seven and a half hours. I loved to have people over for dinner and to make cakes for my friends’ birthdays. I went to museums and plays and got to jump in a cranberry bog for my job. I had a son whom I loved more than anything and a newborn I needed to take care of. This could not possibly be my life.”

Later in the same piece, she expressed gratitude to her family who stayed by her side and searched for a way to cure her. “My parents and my brother and sister, too, have been raising my children and sitting in my various hospital rooms almost every day for the last year and a half,” she wrote. “They have held my hand unflinchingly while I have suffered, trying not to show their pain and sadness in order to protect me from it. This has been a great gift, even though I feel their pain every day. For my whole life, I have tried to be good, to be a good student and a good sister and a good daughter, and to protect my mother and never make her upset or angry. Now I have added a new tragedy to her life, to our family’s life, and there’s nothing I can do to stop it.”

There is an even deeper sadness to this story which few commentators, if any, have picked up upon. I wish to do so, in the spirit of compassion, discernment and collective healing.

Before I begin, I would like to express my heartfelt condolences to the Schlossberg, Moran, and Kennedy families, and especially to the two very young children who will now grow up without the warm embrace, smile, and vibrant intelligence of their dear departed mother. May you all find the strength you need at this challenging time, and in the years ahead.

Returning to the essay published in 2024 in The New Yorker, I, too, know what it is like to live a life trying to be “good,” a life “trying not to show my pain and sadness.” Though often applauded, praised, encouraged, and even considered noble in our culture, it is not something I would recommend to any individual, or indeed to any family, specifically when it involves sacrificing the “True Self” and replacing it with a “False Self”.

Yet, all to often, it is the energy field of cultivating the False Self which emerges in the family system. Surely the ideal family would be one in which we can all unfold and blossom as the idiosyncratic cosmic flowers that we are, as unique as the prints of our fingers.

A family where fears are dealt with in a compassionate and competent manner, where all participants feel a good-enough degree of safety, where healthy conflict is modelled by the adults, such that all members are encouraged to be authentic and assisted to learn to live life on life’s terms, fuelled by love, not fear.

This is not about perfect parenting. We are not saints. It is about “good-enough” parenting. Unfortunately, this has not been and is not available to many children growing up, me included.

It is because, in many families, the parents have not learned to make this shift from fear to love that the children eventually begin to bear the heavy burden of woundedness (trauma) passed on from previous generations. The contemporary mystic and spiritual teacher, Richard Rohr, says we have two options: to either “transform or transfer”.

That which we do not transform, — indeed transcend in our lifetime — gets transferred to the next generation(s). In this respect we now are at a pivotal moment in the history (herstory?) of humanity.

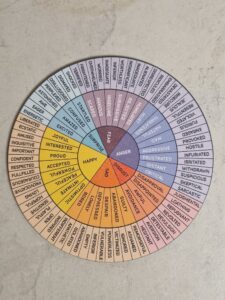

“A miracle is a shift from fear to love,” states Marianne Williamson in her commentary on “A Course In Miracles”. That shift, and the awareness of how it can be achieved, is now spreading through recovery communities like wildfire.

By recovery communities, I mean the movement originally spawned by a bunch of alcoholics in New York City and Akron, Ohio in the late 1930’s which eventually spread around the world as Alcoholics Anonymous. Now, with membership in the millions, there are over 200 fellowships dealing with the plethora of addictions which plague humanity, such as Workaholism, Food Addiction, Gambling, and most recently, Media Addiction, to mention but a few.

All of these fellowships follow the same phases of recovery, i.e., awareness which overcomes denial, belief in a solution, abstinence, compassion (for self — past and present —, others, and circumstances), learning to regulate our autonomic nervous system (through prayer, meditation, dance, exercise, etc.), tapping into energies of frequencies higher than those of the ego, and, ultimately, engaging in new behaviours. We then go on to pass on what has been generously given to us.

“We cannot think our way into new ways of acting, we can only act our way into new ways of thinking”, stated Bill Wilson, co-founder of AA. How true this is! It is being demonstrated in labs all around the world using the latest imaging technology which shows us in real time what is going on in our brains at any given moment.

Every transformation process, in order to be successful, is made up of 20% insights and 80% practice (action). The reason why most fail is that we get plenty of insights and fail to develop and cultivate a daily practice.

While there are now so many fellowships for dealing with addictions, — both substance and process addictions — three, in particular, stand out.

AA is the Father Fellowship, founded mostly by male alcoholics, who wished to quit drinking and subsequently find and execute a better design for living. This was quickly followed by the Mother Fellowship, Al Anon, founded by their wives who realised that they, too, needed their own form of recovery from family dysfunction.

It took some time before the progeny of these two fellowships emerged, namely the fellowship called “Adult Children of Alcoholics”. While so designated, it is specifically designed for all those who wish to recover from the effects of growing up in the chaos of a dysfunctional family, whether their parents were alcoholics or not.

My parents were not. They drank socially and, as far as I know, rarely to excess. Over the last few years of living in the ACA Programme, however, I have arrived at the conclusion that both of my parents were, themselves, adult children of alcoholics. As such, they would have gone through their entire lives in the state of emotional neediness and unexpressed grief that untreated Adult Children must. How could it be otherwise?

They, in turn, could pass on only what they had, — values, ideals, an ethos of public service, a love of nature, a comical sense of humour, — and this they did with passion and great love. While I am deeply grateful for what they gave me, Emotional Sobriety was not something they could master and thus not imparted to me as their child.

With the advent of ACA in the late seventies, a new dimension of recovery began to be explored. Not only do we become free of the bondage of addiction, but we look deeper to identify and transcend the childhood wounds which propelled us into the coping strategy of addiction in the first place.

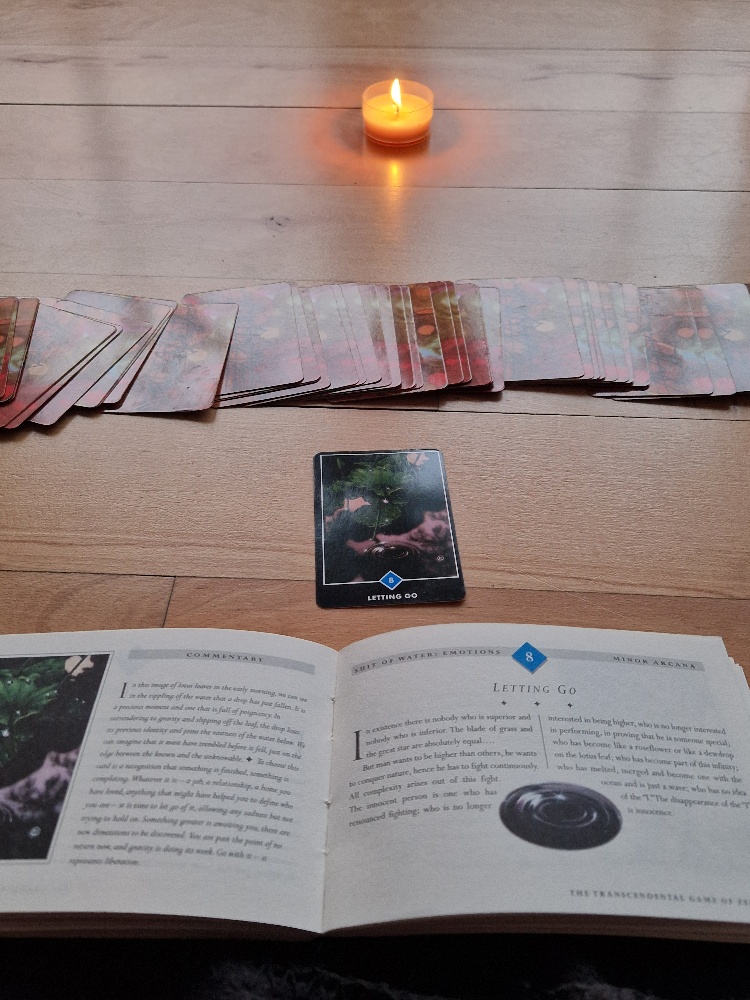

This inevitably involves encountering some or all of the original childhood pain, the grieving of our losses, and the transcending of trauma such that we can relinquish the old fear-fuelled patterns which kept us above water in our formative years, but which no longer serve us today.

The life jacket we donned as five-year-olds (and which kept us alive!) is the same jacket which is suffocating me as an adult today. It is too tight. So, it must be removed, often before we can see what will replace it, if anything at all.

The metaphorical life jacket might take the form of isolating, of excelling at school and sports, of “being good”, or any of a myriad of coping strategies, all driven by the fear of neglect, abandonment, or other forms of woundedness.

The remit of ACA is stated in the “Welcome to ACA” section of the basic text, the “Big Red Book”. It is described as follows: “Adult children are committed to halting the generational nature of family dysfunction for the greater good of the world.”

Thanks to the technological innovations in imaging technology and neuroscience, the clinical research of recent decades, and newly devised body-based therapies for treating trauma (EMDR, Somatic Experiencing, EFT, etc.), we have now at our disposal resources and knowledge which have never been available to previous generations.

With these resources, we can transform the dysfunction which has been passed down through countless generations.

We adults can do the Inner Work of healing the wounded Inner Child and create safe surroundings where our children and our children’s children need not abandon themselves (True Self) to the persona (False Self) which, they figure, has the best chance of garnering the affection and attention they would otherwise miss out on.

This is, therefore, truly a Golden Age, a wonderful time to be alive.